For many of us, work in libraries is not our first profession. How did you make your way to archivist?

I worked at the LBJ Library and Museum all though my community college and undergraduate career, and kept on working there in graduate school during the summers. It was a job both my brother and my sister had had before me, but archives didn’t stick to them like it ended up sticking to me. I went to graduate school for writing and then ended up working as a researcher on a fourth-grade history textbook for the Wisconsin Historical Society, where it was part of my job to look through old photographs and documents. I really liked providing material that made history come alive for people. So, I went to library school and studied to be an archivist.

You were well-steeped in archives before even before going professional. Did anyone in particular inspire you during your training?

I have to thank LBJ! And David Humphrey, a family friend who was an archivist and historian and who introduced my family to LBJ Libraries’ archives. Unfortunately, by the time I started working there, he had moved away. But I truly admired all the other archivists I worked with there and at the Wisconsin Historical Society. Some researchers stick out, too — LBJ’s biographer Robert Caro, of course, plus people studying things I had never thought you could study before. At the LBJ Library, I made copies of documents for researchers, so every day there were mysteries to solve: Why was the researcher looking at this? What stuck out to them?

But most of all, I was inspired by Ciaran Trace, the professor who ran the archival training track at the U of Wisconsin back in the day. She gave us such a wide, fascinating view of archives and their power. I’m so lucky to have studied under her.

How did you make your way to Modern Political Archives at the Baker Center?

I followed my wife from Wisconsin to Knoxville. Getting a job in archives is not easy — I worked for the graduate school dealing with thesis and dissertation formatting for three years before the MPA position opened.

For people who do not work in or with libraries, special collections, or archives, what would you say is the biggest misconception about what an archivist does?

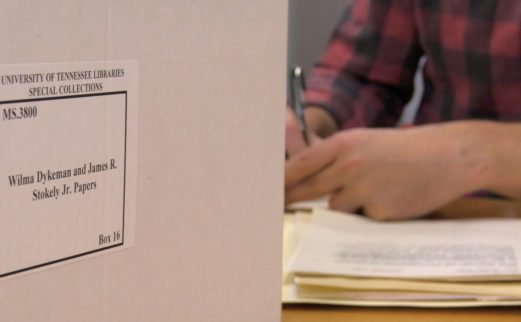

I think most people who work outside of the library and archives (and history) worlds don’t know archives exist. When they find out, often the first question they ask is, “Is everything digitized?” For archivists it goes without saying that not everything is or even will be digitized — that’s not a viable solution. Some historians — especially of the old school — see us as guards who hoard our collections and prevent them from accessing “the good stuff.” In many situations (and I hope most), this is untrue, although some things are fragile enough that they cannot be easily handled, and some things are not available to look at right away, often because of privacy or security issues. We have to balance protecting the materials in the long-term and protecting people, with giving access to archival material. I have never personally met an archivist who didn’t fervently wish their collections to be used. We do what we do so we can make history available.

What kind of researchers visit the MPA?

The researchers who have visited the MPA most recently are independent authors, journalists, and filmmakers. There are also frequent waves of scholars: graduate students and professors.

Do you see any major challenges on the horizon for your profession?

Our profession has been examining our roles through the lens of social justice for a while now. I think we’re much more aware of how we reflect the world and what power we have, and I think we’re learning to harness that power in ways that serve groups who have traditionally been underrepresented and mistreated. At the same time, we’re aware that cuts to funding for education and cultural programs could potentially hinder this work. Also, we have to worry about corporations and other large entities owning and using our personal archives. When we use Gmail, is our information safe in the short term, let alone the long term? And what about the ability to erase evidence of wrongdoing at the click of a button?

Of course, there’s going to be way more work to do with digital records. I’m not sure that will change what an archivist does at heart, but it might change the conversations we have and with whom we have them.

To complete our interview, we have to ask: What is your wish for archivists of the future?

The big dream is that archivists can help reverse injustice by shining a light on the past. My hope for the archivists of the future is that they continue to be fierce advocates for the preservation of our cultural and intellectual heritage, as ugly or as beautiful as it may be, and to remember why we do what we do.