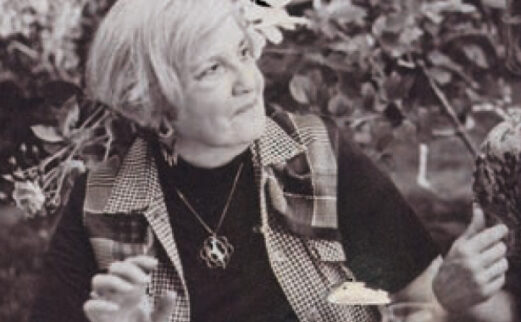

Poet Marilou Awiakta was recently named to USA Today‘s Women of the Century list. The University of Tennessee Libraries holds her papers.

The UT Libraries recently acquired the papers of Marilou Awiakta, adding a new and distinct voice to our primary materials on Appalachian and Cherokee culture.

Marilou Awiakta — listed as Marilou Bonham Thompson in some of her writings — is a Cherokee poet, storyteller, and essayist. She is of Cherokee and Scots-Irish descent, with Cherokee ancestry on both sides of her family tree. Her roots in Appalachia — mostly in East Tennessee — can be traced back to 1730.

Awiakta has said, “My culture has three heritages: Cherokee, Appalachian, and the atom.” She was born January 24, 1936, in Knoxville. When she was nine years old her family moved to Oak Ridge, the fully fenced-in Secret City that was then a production site for the atom bomb.

And now, a few miles away, we had a new frontier.

Daddy went first, in ’43—leaving at dawn, coming home at dark

and saying nothing of his work except,

“It’s at Y-12, in Bear Creek Valley.”

The mystery deepened.

The hum grew stronger.

And I longed to go.

Oak Ridge had a magic sound—

They said bulldozers could take down a hill before your eyes

and houses sized by alphabet came precut and boxed, like blocks,

so builders could put up hundreds at a time.

And they made walks of boards and streets of dirt (mud, if it rained)

and a chain-link fence around it all to keep the secret.

(Excerpt from “Genesis,” Marilou Awiakta)

The poet received her name, Awiakta, meaning “eye of the deer,” from her grandfather. “He said, ‘You have the nature of a deer. You’re a keen listener, gentle and very quick. But I don’t think you should use that name until you’ve grown into it.’ At age 40, after talking it over with the elders and my family, I moved my work over to the name Awiakta.”

Awiakta graduated magna cum laude from UT in 1958 with bachelor’s degrees in English and French. She went on to live abroad, establish organizations dedicated to the betterment of Cherokee peoples, facilitate poetry workshops nationwide for people with varying backgrounds — including formerly incarcerated women — and write nationally recognized books that showcase her life experiences.

Abiding Appalachia: Where Mountain and Atom Meet, released in 1978, details her experience living in Oak Ridge as an Appalachian Cherokee during the creation of the atomic bomb. Her 1983 children’s book, Rising Fawn and the Fire Mystery, tells the story of a young Choctaw girl swept up in the Indian removals of the 1830s. Selu: Seeking the Corn-Mother’s Wisdom, published in 1993, is a collection of poems, stories, and essays about indigenous values and wisdom. She received the Distinguished Tennessee Writer Award in 1989 and the Appalachian Heritage Writer’s Award from Shepherd College in 2000.

Awiakta’s work tells the stories that many of us have heard while living in Knoxville — Oak Ridge, the atom bomb, religion and spirituality, and old Knoxville — but through a different lens. Too often we are told these stories from the same perspectives, in the same voices. The resulting homogeneity is not only mundane — it’s also limited. Viewing any event through the disparate experiences of people from different backgrounds adds dimension and color to the picture.

I rise in silence, steadfast in the elements

with thought a smoke-blue veil drawn round me.

Seasons clothe me in laurel and bittersweet, in ice

but my heart is constant . . . Fires scar and torrents

erode my shape . . . but strength wells within me

to bear new life and sustain what lives already . . .

For streams of wit relieve my heavy mind

smoothing boulders cast up raw-edged . . . And the

raven’s lonesome cry reminds me that the soul is

as it has ever been . . .

Time cannot thwart my stubborn thrust toward Heaven.

("Smoky Mountain Woman,” Marilou Awiakta)

It is important for the Libraries to invest in collecting the stories of the many different people who inhabit this region. When people talk or write about Appalachia — its people, its cities, its history, and its culture — the region is frequently painted with a very broad brush. The images are often negative caricatures, not reality.

By collecting the stories of all the communities that inhabit this region, libraries can help change the narrative. In fact, that work is the express duty of librarians. The American Library Association’s Library Bill of Rights states that “the publicly supported library provides free, equal, and equitable access to information for all people of the community the library serves.” The community we serve at the UT Libraries includes Native American peoples, and the land that we occupy is Cherokee territory.

Academically, a more diversified collection benefits all of our patrons and researchers. The more, and more varied, information we provide researchers, the better the quality of research they can conduct for the betterment of different disciplines. As a top research library, we aspire to be a leader in supporting broad collections that reflect different cultural perspectives.

We are grateful to Marilou Awiakta for entrusting her papers to the UT Libraries. We hope her gift will draw further donations that broaden our special collections. There are many more voices to be heard.

Quotations are from “Marilou Awiakta: Internationally Acclaimed Native American Poet, Storyteller, Essayist,” Memphis Downtowner Magazine [n.d.], accessed June 1, 2019, http://www.memphisdowntowner.com/my2cents-pages/Marilou-Awiakta.html. Poems appear in Marilou Bonham Thompson, Abiding Appalachia: Where Mountain and Atom Meet (Memphis: St. Luke’s Press, 1978).