The UT Libraries’ Diversity Committee hosts conversations on issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion — most recently on the issue of living with a disability.

“I recently learned that in the 1970s … Cambridge University refused to build a ramp for Stephen Hawking, the very famous physicist, so that he could get into his own office,” Leigh Mosley remarked at the virtual panel discussion on September 28. Even the world-renowned theoretical physicist — who suffered from ALS — had to fight with his employer to gain accommodation for his disability.

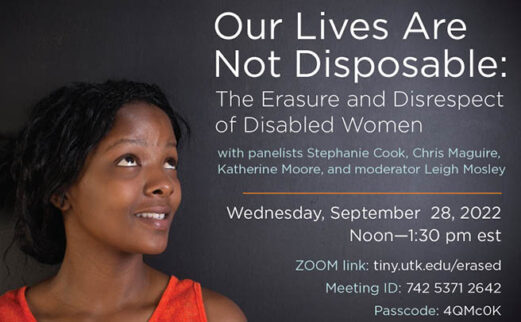

Mosley, the UT Libraries’ Accessibility Coordinator, was moderating a panel of three women who are disability advocates and who, themselves, live with disabilities.

Although the disability community has secured many rights over the past 50 years, ableism pervades our culture.

Ableism is “a system that places value on people’s bodies and minds based on societally constructed ideas of normality, intelligence, excellence, desirability, and productivity.”*

Deep-rooted attitudes that devalue the lives of the disabled have real-world consequences. When the COVID-19 pandemic reached the US in early 2020, the state of Tennessee had some blatantly discriminatory guidelines in place for dealing with a public health emergency. Tennessee’s 2016 Guidelines for the Ethical Allocation of Scarce Resources would have excluded people with certain medical conditions from receiving scarce medical resources on the assumption that those individuals would be less likely to respond to treatment.

Stephanie Cook, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Coordinator for the City of Knoxville, recounted the response from the disability community in Tennessee. “Disability advocates went bonkers! … Disability Rights Tennessee and some other agencies marched right down there to the state capitol and educated folks… And the Governor’s office and the state legislature worked with them to change that law. That’s a good thing. But really! In 2020, should there be anything out there like that on anybody’s legislative book!?!”

Mosley asked, “Why does it seem that people who make public policy never seem to have any visible health issues themselves? It seems like there is no representation of — quote/unquote — ‘medically fragile people’ on these boards that make literally life-or-death decisions for the medically fragile people.”

“It’s getting better,” Cook said, “but rarely do you see those most impacted by policy represented on the boards or the commissions that create those policies.… I always encourage people: If there’s something that’s of interest to you, and you live in an area where the mayor or the council or whomever has a committee or a board that’s dedicated to this issue that’s important to you, go to that meeting. Do their survey. Show up. Say, ‘I want to be a part.’ Volunteer and get involved. Because, until people with disabilities — those who live with disabilities or those who are connected closely with people who live 24/7 with a disability — start making these policies and being on the boards that make these policies, these issues will never change.”

But, Cook pointed out, there’s a “catch-22.” Community boards may welcome members with disabilities, “but beyond offering a space that’s physically accessible for somebody in a chair or with a cane — that’s all you get. You don’t get braille or large print or an interpreter and whatnot. And so sometimes there are arms wide open: ‘Y’all come, we want the disability community involved — but it has to be those people with disabilities that we know how to accommodate…’”

“The ones that don’t cost us extra money,” Mosley quipped. “Do you know anyone with inexpensive disabilities?”

“I don’t know inexpensive humans!” was Cook’s retort.

Discussing the hurdles faced by disabled people who run for elected office, Katherine Moore, Executive Director of the disABILITY Resource Center serving Knoxville and southeast Kentucky, said: “You’ll have to get rid of the stereotypes and myths. Because, if somebody with a disability runs for office — let’s say, somebody with a physical disability that can be seen… it’s doubly hard for them to get elected because they have the stereotype and myth that goes along with their disability. So, they not only have to prove that they can do the job they also have to prove that they can think for themselves, they can take care of themselves.… People may think that’s all they’re interested in, too. Just because you have a disability doesn’t mean you’re not going to be interested in all the other issues that occur. You’re going to have that stereotype, too: ‘Well, they’re just going to serve the disability community or the disability population and not serve everybody.’ And that’s not true either.”

Certainly, laws and public policies that disproportionately impact the disability community should be reexamined. Fortunately, the most egregious US laws from the early 20th century have been repealed — such as laws inspired by the eugenics movement that allowed forcible sterilization of those considered a burden on society.

“There have also been other laws that penalize people for being disabled,” Cook told the audience. “They penalize people with disabilities [in that they] won’t allow them to choose to live their lives the way others without disabilities would. For example, oftentimes, if two individuals with disabilities who are receiving income from the Social Security Administration because of their disabilities, and they get married, then there’s a chance that their benefits could go down. Some people have to remain single and can’t get married in order to maintain the level of medical care that they’re getting.”

Other barriers prevent disabled individuals from accessing public services readily available to others.

Statistics show that disabled individuals suffer domestic violence at a higher rate than the general population. Yet, Moore explained, shelters often turn away the most vulnerable. “If they have a physical limitation, if they’re a wheelchair user, if they’re a person who’s deaf, if they’re a person who’s blind, the shelters won’t take them. They refuse to take them. They make it much harder than it is to have a person in a shelter with a disability.… This is being allowed. This is not being addressed. And it’s not being addressed by the people who provide the services. They don’t make the shelters accessible. They don’t want to counsel with or work with the women (and men) with disabilities that are going through domestic abuse — because they can’t get past the disability part. They don’t need counseling or help or assistance — quote ‘with their disability’ — as long as the shelter is accessible. What they need is counseling and therapy and services the same as anyone else without a disability …”

The pandemic has shone a light on the barriers faced every day by people with disabilities. And “long COVID” has meant that millions of people have suddenly found themselves disabled.

But the pandemic also highlighted ways that we can make reasonable accommodations for workers. During the peak of the pandemic, everyone was seeking a safe working environment. Employers recognized that many jobs can be done remotely. As long as the job can be accomplished via telecommuting, staff can safely work from home without sacrificing productivity — as members of the disability community have argued for years.

What if you need accommodation for a disability and your employer is no longer willing to offer you the option to work remotely, now that the peak of the pandemic has supposedly passed? “Change jobs!” advised Chris Maguire, a former University of Tennessee staff member who now works at Vanderbilt University. “Change jobs! There are people out there who will appreciate you and allow you to work remotely and value you for your skills.”

Mosley ended the discussion by asking, “What do you wish people would do differently?”

“In a perfect world… why can’t people just be who they are?” Cook asked. “If they look different, if they sound different… Who cares? I would love to see a society where we just accept people for who they are… and move on.”

“Right now,” Cook said, “there are approximately 61 million Americans with a disability… In our country today, ten thousand individuals turn 65 every day. Not to say that when you hit a certain odometer reading you’re going to have a disability! But chances are you’re going to lose mobility, eyesight, hearing… If we leave with some overwhelming message, I hope that it is: People with disabilities are all around us. We are all going to be a person with a disability at some point. So, I refer to us as temporarily able-bodied.… Just be mindful that the more any of us can do to be inclusive, to raise our hand and say, ‘Well, why are people with disabilities not invited to this? Where are people with disabilities at the table helping us make this decision?’ — We can all do this work, if you will, to make sure we’re all able to participate.”

__

*Talila Lewis, talilalewis.com/blog/january-2021-working-definition-of-ableism, accessed September 29, 2022.