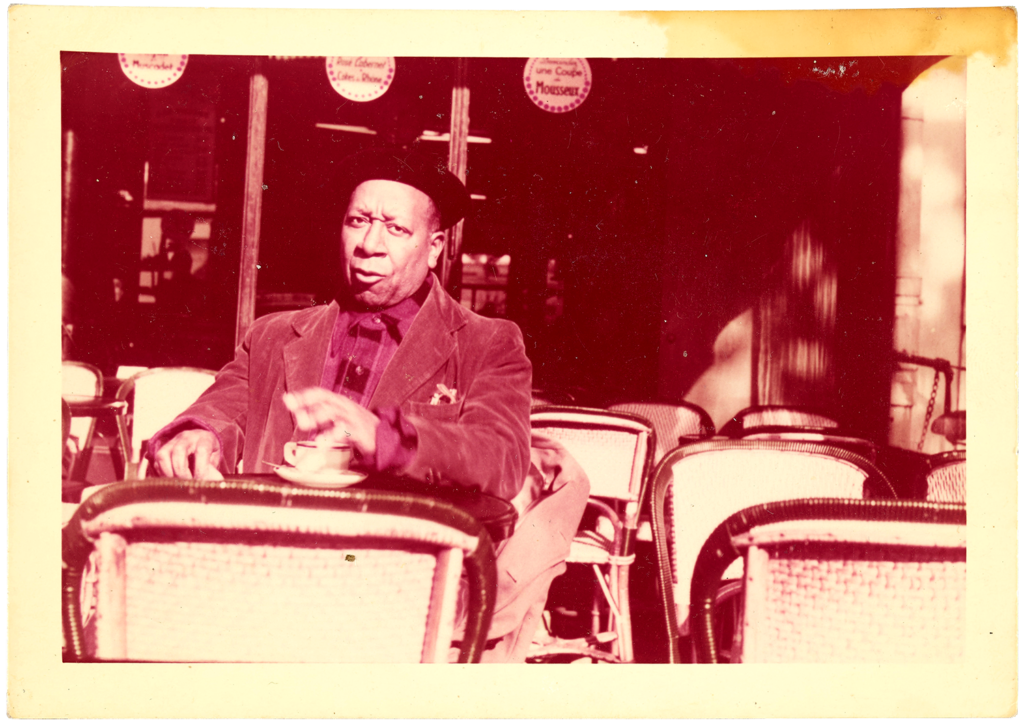

Knoxville-born artist Beauford Delaney’s colorful portraits and vivid abstractions can be viewed in the National Portrait Gallery, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Knoxville Museum of Art, among many other places. Delaney’s paintings capture the profound and striking way he saw the world, conveying layers of meaning that transcend language.

The UT Libraries’ collection of Beauford Delaney’s papers is important because it opens a pathway to seeing his world through a new lens. Through writings in his journals, letters to and from his friends and family, and materials he read and collected, art lovers can explore more of what Delaney saw. The collection also includes works of art that, in the context of an archival collection, might be regarded as both art and artifacts.

For the UT Libraries research team, a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation provided another way of experiencing Delaney—seeing the world through Delaney’s eyes.

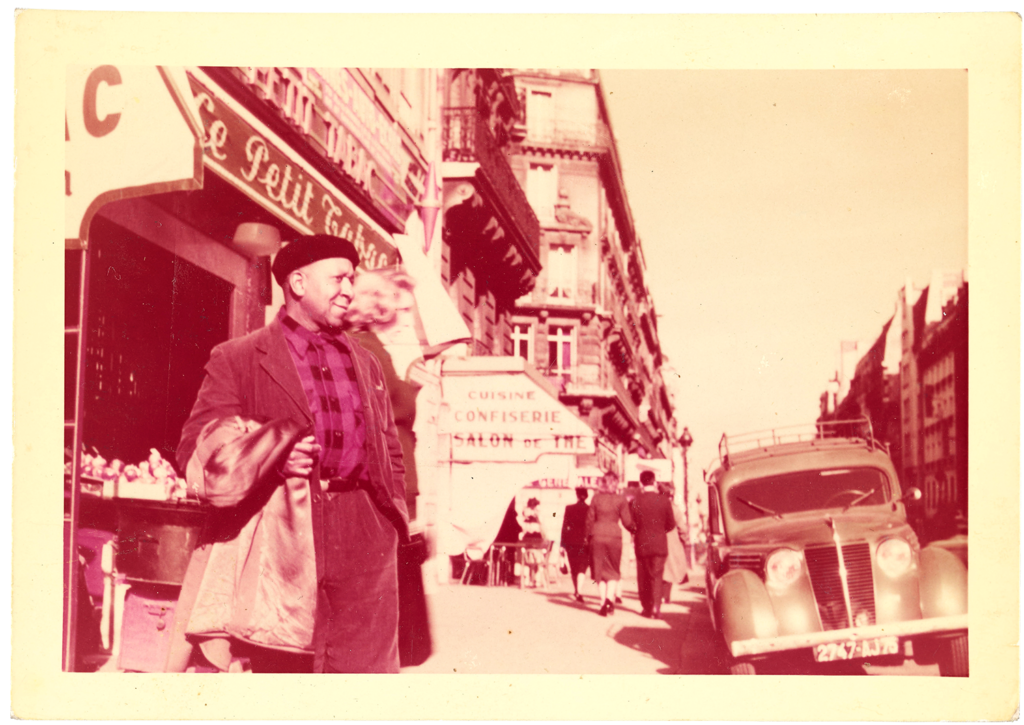

Although he never intended to stay in Paris, France, Delaney spent the last 25 years of his life in the City of Light. There he found inspiration, home, and community. In his biography Amazing Grace: The Life of Beauford Delaney, David Leeming says that in Paris Delaney could “discuss Cezanne, and Renoir, and Picasso, and Matisse in the very streets where they had been.”

UT’s grant-funded research team was composed of Katrina Stack, a PhD candidate in geography; Kris Bronstad, archivist and associate professor; Holly Mercer, senior associate dean of libraries; and Jennifer Beals, assistant dean and director of the Betsey B. Creekmore Special Collections and University Archives. For three and a half weeks, they followed Delaney’s footsteps through the very streets and cafes he once frequented in the French capital. They had identified many of those places through the Beauford Delaney Papers, housed in UT Libraries.

Influenced by scholarship in the subfield of Black geographies, Stack, who is the research fellow for the Beauford Delaney Papers, hopes to use the collection and the experience in Paris to provide insight into Delaney’s “Black sense of place”—a concept from scholar Katherine McKittrick—in the spaces he moved through and inhabited.

From the time he arrived in Paris in 1953 until his death in 1979, how did Delaney, a Black queer artist from the United States, experience Paris? In what spaces was he welcomed—and with whom?

Approaching Delaney with a geographic perspective not only grounds Delaney in place—Knoxville, New York City, Paris—but also offers a way to center his narrative, which has too frequently been placed at the periphery of those important in his life, such as James Baldwin.

In an effort to bring Delaney’s story to the forefront, the research team enlisted the help of Monique Wells, a long-time resident of Paris originally from the United States. For over a decade, Wells has been documenting and sharing Delaney and his connections in Paris and elsewhere. She has led multiple successful efforts to commemorate buildings where Delaney lived. After discovering his final resting place in a large cemetery outside of Paris, Wells rounded up the support necessary to finally place a headstone on his grave. Her company, Entrée to Black Paris, conducts walking tours of the city that focus on influential figures like Delaney, Baldwin, Josephine Baker, and Richard Wright. Wells makes deep and meaningful connections between those artists and the places they moved through in Paris, shedding light on how the city influenced them and their work. Her blog, Les Amis de Beauford Delaney (lesamisdebeauforddelaney.blogspot.com), is one of the most important and accessible resources for anyone interested in Delaney.

Before their trip to Paris, the team shared with Wells a list of addresses recorded in documents from the Beauford Delaney Papers. Addresses were pulled from hundreds of letters, exhibition records, and an address book friends had compiled and gifted to him. The locales were the art galleries, cafes, and homes where Delaney spent his last 25 years. Wells used the list to develop a new version of her tour around the Boulevard Saint-Germain with heightened focus on Delaney, highlighting sites in the blocks around that street and the Luxembourg Gardens.

Wells’s passion is to take people to physical spots where cultural events took place: This is where Delaney lived. This is where Delaney spent hours talking with friends who were also artists and thinkers.

Wells places the tourists there and asks them to engage in an act of imagination, to access their own experience of that history. Her tour of Beauford Delaney’s Montparnasse neighborhood took the research team to many places of significance for Delaney in that area, such as Café Le Select. Near the Boulevard Saint-Germain she escorted the team to the location of what had been Galerie Prismes, where Delaney had his first show in Paris, and she guided them to Delaney’s final resting place at Thiais Cemetery. The team explored some locations on their own, including Delaney’s home in the Paris suburb of Clamart. Those spaces provided spatial context to familiar documents, connecting resesarchers to the past and place through the physical landscape and an act of imagination.

The exploration of a historically meaningful physical space is like the archival exploration researchers undertake in the Special Collections reading room. To really understand what information is being communicated in archival documents, researchers consider context. For correspondence: Who was speaking of or being spoken to? For exhibition invitations and catalogs: Where did Delaney show his work? What shows and galleries was he invited to? Engaging with these questions requires similar acts of imagination and inference. Both physical and archival explorations provide the scaffolding from which to gain greater insight and understanding, strengthening connections to the past.

The UT Libraries’ research team experienced archival and physical exploration simultaneously when they visited several Paris archives and libraries that house Delaney-related materials. In the French National Archives, team members saw Delaney’s letters to art critic Alain Grenier. Some matching puzzle pieces—Grenier’s responses to Delaney—are in the Beauford Delaney Papers at UT Libraries. Looking at the papers of another art critic at the Pompidou Centre’s Kandinsky Library, the team accessed background materials that went into a seminal article—published side-by-side in English and French—about American artists in Paris (“The American’s ‘Gay Paris’” by Julien Alvard, Cimaise, July–October, 1964) as well as the Delaney-centered notes and sources that went into another groundbreaking Alvard article situating Delaney within a global art movement.

Also in the Kandinsky Library’s archives were newspaper clippings that alerted the team to the dilemmas facing Delaney’s friends who were concerned for his care in the later years of his life. In the Pompidou Centre’s collection, they saw some exhibit materials that are duplicated in the UT Libraries’ collection as well as materials that UT does not hold—for instance, a copy of Tributary: Poems, a 1999 book of poetry by Cid Corman that was inspired by Delaney and his work.

While the team crossed through several Paris arrondissements on the Metro, they also navigated the processes and barriers of entering foreign archives, many of which are exclusive to university-affiliated researchers. Requiring such affiliations limits access to the documents housed in those repositories for people like Monique Wells, whose work is public facing and educates visitors to Paris but is not directly connected to an institution. As the team accessed the documents in those spaces, they recognized the importance of having so much Delaney material in UT Libraries that is accessible to all.

Most of the materials in UT’s Beauford Delaney Papers can’t be found anywhere else in the world. Thus, UT Libraries must consider how to make those treasures more visible and useful for researchers in Delaney’s hometown of Knoxville and beyond. How can UT Libraries further the impact of the remarkable way this important artist saw the world? How can UT Libraries and others use this collection to elevate his legacy?

For the near future, UT’s research team members are excited to promote Delaney through both physical and digital exhibits. They hope to welcome researchers and visitors from around the globe, including Wells, and joining them in finding inspiration by encountering the past through the medium of geography.

Photos of Beauford Delaney from the Beauford Delaney Papers, MS.3967, Betsey B. Creekmore Special Collections and University Archives, University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Estate of Beauford Delaney by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court-Appointed Administrator.